The Valuable Employee Paradox

Here’s a seeming paradox:

Every great manager I know tells me that the reports they find most valuable are the ones who convince them to do things differently.

However, most reports believe they are most valuable when they do what their manager wants.

These axioms have been true in hundreds of promotion discussions I’ve been a part of. They’ve been true in my own life. The people I value the most are the ones who regularly challenge my thinking to present different and better ideas.

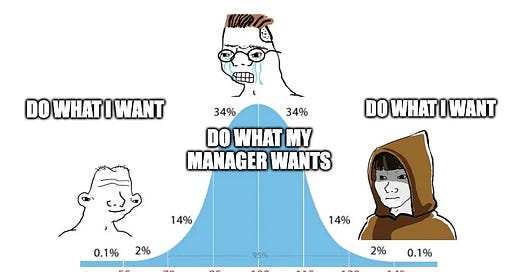

So how do we circle this square? I present to you the midwit curve, which is my favorite encapsulation of everything in life:

The worst reports…

…do what they want but in a way that goes against the team’s interests.

These are the folks who blow past deadlines because the sequel to their favorite video game just came out that week. The ones who put up an “off-the-grid” message right after checking in a massive buggy commit. The ones who decline a double-digit percentage of meetings because they’re slightly inconvenienced—it’s too early, or too late, or they’re too hungry, or their brains are too fried.

Since a manager’s job is to make teams successful, a member who lets the team down because they are optimizing for themselves is obviously a thank u, next.

The average reports…

…support and do what their manager says. If the manager goes, “Let’s do Project X” they shrug their shoulders and ask “When?” and “How?” even if Project X is kinda loony.

There are a few reasons why folks adopt this strategy:

They are optimizing for promotions and they genuinely believe that “Do what my manager says” is the best path to attain that.

They are optimizing for team success but they genuinely believe their manager always makes higher quality decisions than they do.

They are optimizing for comfort / ease and thus prefer to avoid the energy-consuming work of critically evaluating how they feel about Project X.

Since a manager’s job is to make teams successful, this type of “yes-boss” report is generally useful to have around. They are reliable. They get shit done. They don’t spin up drama.

However, their presence doesn’t do much to strengthen the team. In fact, the team’s success is fragile, banking entirely on the quality of the manager’s judgements.

The best reports…

…do what they want but in a way that furthers the team’s interests.

If the manager goes, “Let’s do Project X” they ask themselves, “Is Project X smart or loony?” If they think it’s loony, they dig further until they either a) now believe it’s smart or b) propose an alternative that’s smarter.

Even if they do support Project X, they ask, “Am I the best person to work on Project X?” If yes, then they’re all in. If not, then they volunteer for some other project.

Since a manager’s job is to make teams successful, these keen people who peer critically at plans with the goal of spotting and strengthening holes are worth more than a truckload of rubies. Most CEOs I know would trade multiple “Yes-boss” types for a single one of these Jedi.

So, what does this mean for you?

If you want to be a top performer, if you want to be a leader or among the most valued folks at your company, you’re probably not going to get there by yes-bossing (unless your workplace is one of those super hierarchical types).

Instead, to become a Jedi, you’re going to need to:

a) care a ton about your team’s success

b) develop excellent judgement

c) do things your manager isn’t directing you to do because you care about your team’s success.

The good, bad, and ugly of hierarchy

What’s wrong with workplace hierarchy? Aren’t we humans by nature hierarchical?

Before we go critiquing hierarchy, let’s first define it:

A hierarchy is an arrangement of items (objects, names, values, categories, etc.) that are represented as being "above", "below", or "at the same level as" one another (from Wikipedia)

In a workplace setting, this is generally taken to mean that some employees are considered above, below, or at the same level as others.

This is nothing earth-shattering; after all, it’s no secret that CEOs are higher in level than other employees, and that the Board is higher even than the CEO. On the flip side, at the lowest rung of the ladder we have the intern.

But what do we mean when we say “level?”

One common definition is the power to decide. For example, a CEO can choose to fire Bob. An intern can’t fire Bob.

This power to decide is useful because imagine if the intern, Bob and the CEO disagreed on whether Bob should be fired. They’d talk in circles until the cows came home, which would be wildly inefficient! So one way to cut the conversation short is to assign a decision-maker. Hooray! Now someone makes the call and we can all move on.

But hang on. We don’t just want fast decisions, we want great decisions, decisions that propel our company into the starry echelons of success.

Most of us would agree that a CEO likely has better judgement than an intern on whether firing Bob is a smart decision for the company. So another job of hierarchy is to identify and enable the most qualified people to make the best decisions.

If we lived in perfectly perfect hierarchy, all of us can sleep easy trusting that our CEO would always make better decisions than a VP, who would always makes better decisions than a director, who would always make better decisions than a senior, who would always make better decisions than a junior, who would always make better decisions than the intern.

Alas.

Alas, alas. I hope you can see how laughably far we are from that world.

The reason the Valuable Employee Paradox exists is that company hierarchies are far from perfect.

While a CEO is expected to make higher-quality decisions than a VP of Engineering on matters such as How to hire a CFO?, Should we move our product upmarket or downmarket?, Should we merge with Company Y?, the VP of Engineering is typically better equipped than the CEO to decide Where should we look for the best engineers?, Should we use a streaming or non-streaming database? Should we fire Bob the engineer?

You see this pattern recursively down the entire organization. An engineering director may be better positioned to know the ins-and-outs of the Android platform than an engineering VP. A senior engineer with a background in machine learning may create a better ranking model than a director. A junior engineer may fix a bug in a code base they know well faster than a senior engineer.

Whatever well-meaning system of levels or titles a workplace may come up with, it simply cannot encapsulate all the nuances of good judgement that come from skill and domain knowledge.

If you become a zealous adherent to the idea of hierarchy—a person at a higher level will make better decisions than a person at a lower level—you’re going to be wrong. A lot. Being hierarchical is a mindset—company cultures can be overly hierarchical, and so can individuals.

A strongly hierarchical company CAN operate well if the higher level folks are humble and self-aware enough to know when they should make the call and when to defer decision-making to someone else. But if they aren’t self-aware, or the problem space is highly complex (which leads to greater % of unknown-unknowns and therefore worse judgement of who knows what best), then the higher-level managers will make a lot of shitty calls. The company will eventually pay the price.

The point of any system of hierarchy is to enable faster, better decisions. Things get bad and ugly when people forget that.

There are 3 more chapters in this issue for paid subscribers

Is your workplace too hierarchical? A checklist.

Are you too hierarchical? A checklist.

The antidote to hierarchy

Big thanks to all my paid subscribers! You all keep this newsletter going.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Looking Glass to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.